Boats on the Hooghly River in Calcutta.

Credit: Unknown Author via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Grade: 6-9Subject:

U.S. History, Social Studies, English Language Arts

Number of Lessons/Activities: 4

The first significant settlement of South Asians in the United States was a community of Bengali Muslim peddlers who, beginning in the 1880s, traveled from India to the United States to sell goods. While many of these peddlers intended to return to India, others continued traveling around the world. Those who stayed in the United States embedded themselves within local communities of color. In this lesson, students will learn about the history and motivations of these early Bengali peddlers. Students will also examine the significance of New Orleans, Louisiana to this community.

Students will:

- Examine the geography of regions in South Asia and the American south to explain the settlement of Bengali peddlers.

- Identify causes of and motivations for the settlement of Bengali peddlers in New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Describe the experiences of early Bengali peddlers in the United States.

Bengali Muslim Peddlers in New Orleans Essay:

Bengal refers to a region in the northeastern part of India. (Today, it is divided into the Indian state of West Bengal and the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Most of the people in West Bengal are Hindu with a significant Muslim population. Most of the people in Bangladesh are Muslim.) During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Bengali people were affected by many hardships. They suffered from decreased crops, shortage of jobs, high rents, high debts, overpopulation, and more. In addition, they suffered natural disasters. This included famines, floods, and earthquakes. British

colonial policies such as high taxes made living conditions even harsher. As such, many Bengali people left India. They sought economic opportunities elsewhere.

In the 1850s, Hindu merchants from India had already been traveling around the world. The first Indian merchants to venture into the United States were from an Indian Muslim community. They became the first significant

settlement of South Asians in the United States. This community of Bengali Muslim

peddlers began arriving in the 1880s. They traveled from British India to the United States. They sold goods such as

handicrafts, embroidered silk and cotton

textiles. These “exotic” goods were in great demand in Europe, Australia, South Africa, and the United States. The Bengali peddlers were from Hooghly. (Hooghly is a district in the Indian state of West Bengal.) For generations, women from this area made finely embroidered silk and cotton fabrics. They practiced an intricate style known as

chikan. Small groups of men from villages in Hooghly would serve as traders or

chikondars. They traveled to many places selling handkerchiefs, bed linens, tablecloths, and more.

The travel route of the Bengali pedders involved going to Calcutta and taking a boat to England. Sailing to the United States, their port of entry was Ellis Island in New York. There, they were inspected by medical and immigration officials. Inspectors determined whether they were to be

docked,

detained, or

deported. If granted entry, they would start selling their goods in New Jersey. Beach boardwalk towns in New Jersey were popular vacation sites. During the summer season, hotels, beaches, and amusement parks drew hundreds of thousands of vacation-seekers from nearby cities.

The Bengali peddlers established businesses in the United States. They sent money back to their villages. As this system became more lucrative, the number of Bengali peddlers increased. Some of these peddlers returned to India at the end of the summer. Others continued to expand their reach in the United States. Among their important destinations was New Orleans, Louisiana.

In the late 19th century, New Orleans was a major hub for travel and transport. The port of New Orleans was the second busiest in the country. New Orleans was connected by rail to every major city in the South, North, and West. It also connected the United States to the Caribbean, and Central and South America. It was also a major tourist attraction. It was full of peddlers and neighborhood markets. The French Market was the main marketplace. It had stalls and vendors representing every one of New Orleans’ diverse communities. Bengali peddlers sold their goods alongside German, French, Chinese, Jewish, Spanish, Irish, English, Filipino, Italian, Cuban, Creole, Mexican, African, and Native American merchants.

Census records show that groups of Bengali peddlers shared apartments on St. Louis Street. This was walking distance to where they would have done business. In addition to the French Market, Bengali peddlers worked in the commercial district along Canal Street and the railway terminal on Rampart Street. They had a notable presence. Local newspapers even published stories about them.

This Hooghly network of Bengali peddlers expanded through the southern United States. Small groups settled in cities like Charleston in South Carolina, Savannah and Atlanta in Georgia, Jacksonville in Florida, Memphis and Chattanooga in Tennessee, Dallas in Texas, and Birmingham in Alabama. They also ventured farther south into the Caribbean and Central America.

The peddlers’ lives were largely

transitory. They moved around the world based on consumer demands. They moved where they could do business. They moved according to the seasons. They also moved to where they were permitted to enter. These workers initially did not intend to stay permanently. Most eventually returned to their home villages. Some spent extended periods of time in the United States. However, later, instead of returning to India, more and more of the Bengali peddlers remained in the United States.

Those who stayed had to navigate a complicated racial landscape. During this time

Jim Crow laws were in effect. These laws

segregated every part of public life. This included transportation, schools, and hospitals. There was also a dramatic upsurge in

lynchings of Black men.

In the 1890s, cities like New Orleans, Charleston, and Savannah enforced segregation but were also tourist destinations. This offered communities of color more, albeit limited, economic opportunities. White tourists held fantastical images of “the

Orient.” These images portrayed Asia as exotic and foreign. As such, these cities were perfect locations for the Bengali peddlers to perform “Hindoo”-ness.* They did this in order to sell their goods. They deliberately appealed to White fantasies of India. They wore

turbans and

fezes to look more exotic. They told “quaint” stories of their homelands. They performed politeness and servility to White customers. This performance of being “Hindoo” fulfilled White tourists’ narratives. This also helped the peddlers survive in the U.S. South during one of the most violent times for people of color. Being “Hindoo” versus being “Black” may have provided them more safety and freedom.

Nonetheless, the peddler’s brown skin still made them distinct from White people. Ultimately, the laws and norms of the segregated South still restricted them. They were limited to living in certain areas. They received poor healthcare. They had limited access to public facilities. They also faced discrimination and harassment. As such, many of their operations were often anchored in Black neighborhoods. There, the Bengali peddlers built communities. They married into the local families. The women of color who married these traders also became a part of the Hooghly network. They did the daily labor of maintaining boarding houses, businesses, and families. By the 1920s in New Orleans, Bengali peddlers had integrated into the life of Tremé. (Tremé is a district in New Orleans. It is the oldest Black neighborhood in the United States.)

For more than three decades, the Bengali peddlers were a continuous and visible presence in the state of New Jersey, the city of New Orleans, and other parts of the U.S. South. The Bengali Muslim peddling business declined around the 1930s. This was likely due to the Great Depression (1929-1939) and changes in the textile industry which shifted to the mass production of cheaper goods. Understanding the experiences of the Bengali Muslim peddlers allows us to see how expansive these early circuits of migration were. It also allows us to better understand the strategies migrants employ to survive. Their history demonstrates how a community with a seemingly temporary presence became enfolded into the American story.

*Hindu is the correct spelling. But the spelling “Hindoo” was often used in the 1800s. This term was used to describe Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, reflecting the general ignorance of their diverse faiths. Today, the spelling “hindoo” is considered derogatory.

Bibliography:

Bald, Vivek. “Out of the East and into the South,” Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of Asian America, Harvard University Press, 2015.

Bald, Vivek. “Between Hindoo and Negro,” Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of Asian America, Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Census: a counting of the population (as of a country, city, or town) and gathering of related statistics done by a government; in the United States, the Census takes place every 10 years.

- Colonial: relating to an area over which a foreign nation or state extends or maintains control

- Deport: to force (a person who is not a citizen) to leave a country

- Detain: to hold or keep in, or as if in prison

- Dock: to be allowed to land or enter a place

- Fez: a brimless, round red felt hat that has a flat top and a tassel, worn especially by men in eastern Mediterranean countries

- Handicrafts: objects made in a traditional way with skilled hands rather than being produced by machines in a factory

- Jim Crow Laws: state and local laws enforced in the Southern United States between the late 19th and 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation and limited the rights of African Americans

- Lynch: to kill by hanging by mob action without legal approval

- Orient: an outdated term that traditionally refers to the regions and countries to the the east of Europe, specifically Asia; this term is tied to Orientalism, a field of study that holds stereotypical and often exoticizing views of Eastern cultures, particularly in relation to the West

- Peddler: someone who travels about with wares for sale

- Segregation: the practice of separating or isolating by race, class, or group (as by restriction to an area or by separate schools)

- Settlement: the act of, or the place of, a group of people staying to establish residence

- Textiles: woven, knit cloths

- Transitory: lasting only a short time

- Turban: a man’s headdress, consisting of a long length of cotton or silk wound around a cap or the head, worn especially by Muslims and Sikhs

- Why did Bengali Muslim peddlers travel to the United States beginning in the 1880s?

- Who were the chikondars?

- What is Hooghly and why is it significant?

- Why was New Orleans an important destination for the Bengali peddlers?

- Why did the Bengali peddlers travel throughout the southern United States and farther south into the Caribbean and Central America? What were their motivations for moving from place to place?

- How did the Bengali peddlers navigate the racial landscape of the segregated South?

- How and why did the Bengali peddlers perform “Hindoo”-ness as a means to survive? What does this performance convey about the stereotypes White Americans may have held about people from India?

- How were the Bengali peddlers still limited by the laws and social norms of the South?

- How did these Bengali peddlers embed themselves in communities of color, such as Tremé?

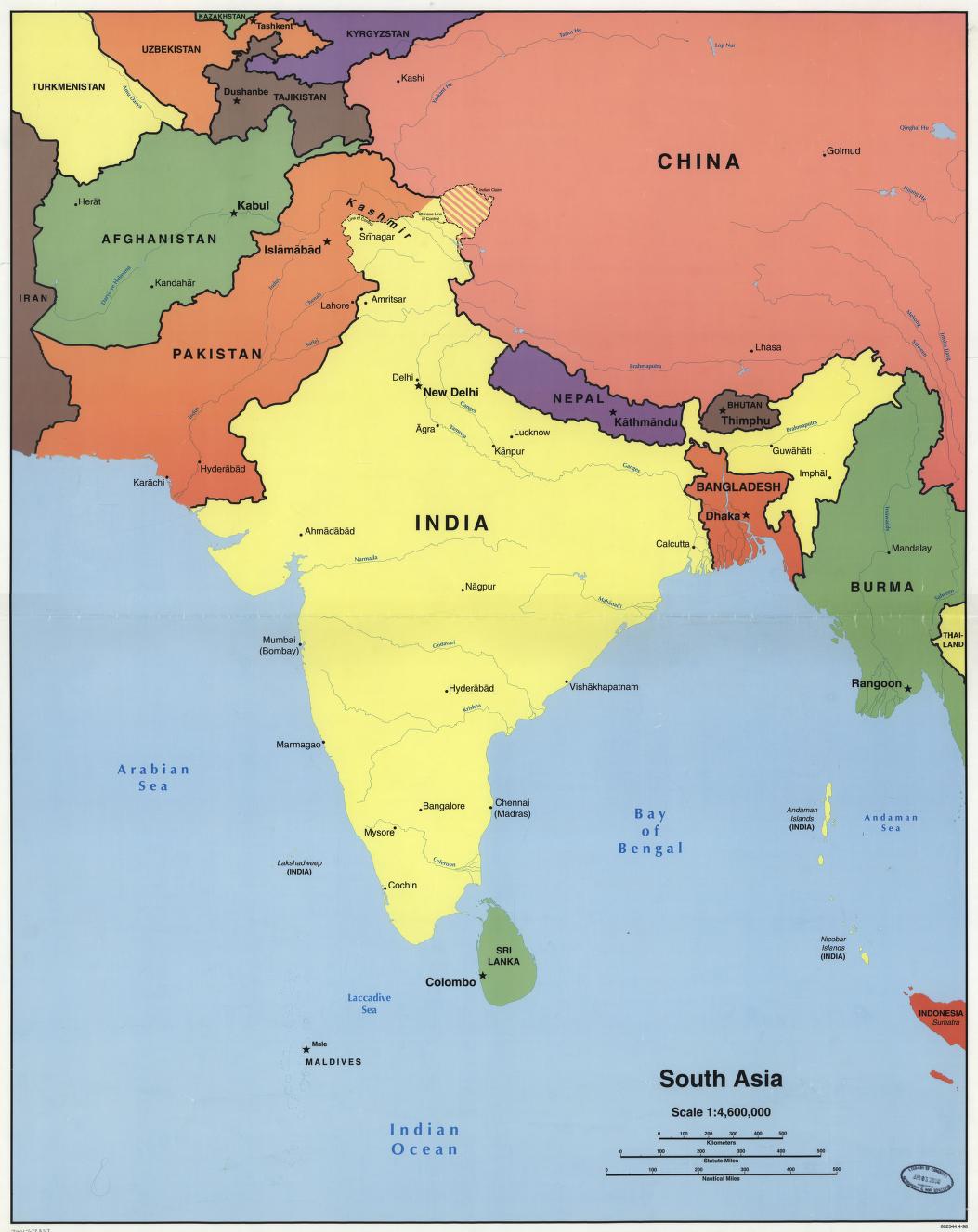

Map of South Asia.

Credit: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Activity 1: Examining the Geography of the Bengal Region

- Show students a map of South Asia. (Or use Google Maps.) Have students share what they know about South Asian and/or the history of South Asian immigration to the United States.

- Tell students the following: “The first significant settlement of South Asians in the United States was a community of Bengali Muslim peddlers in the 1880s.”

- Have students use a map to find West Bengal and Bangladesh. Tell students the following: “Today, West Bengal is a state of India, and Bangladesh is a sovereign nation. But prior to the 1905 Partition of Bengal, this was one region. The eastern area was predominantly Muslim and the western area was predominantly Hindu.”

- Have students use a map to find Hooghly. Have students identify some geographical characteristics of Hooghly based on the map. Point out that Hooghly is bordered by the Hooghly River on the east.

- Show students this video entitled, “Europe on Hooghly River.”

- Ask students: “How might Hooghly’s location be conducive to trade?”

- Tell students the following: “The district of Hooghly was known for silk and cotton embroidery. We will learn how peddlers from Hooghly ended up in the United States.”

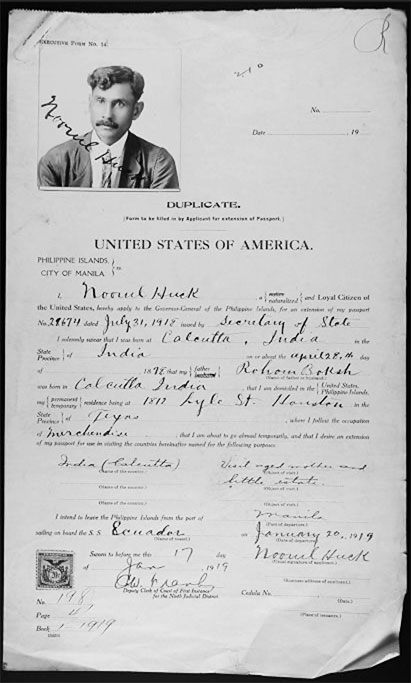

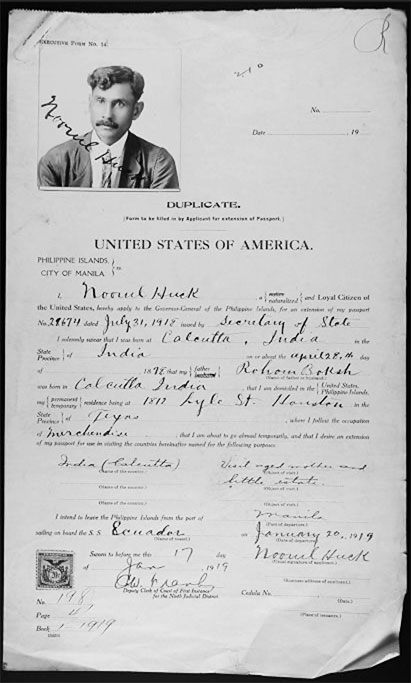

Passport of Noorul Huck, a Bengali immigrant to the United States.

Credit: National Archives, NAID: 143589373

Activity 2: Learning about the Motivations of the Bengali Muslim Peddlers

- Have students read the essay. Consider the following options:

- OPTION 1: Have students read the essay independently either for homework or during class time.

- OPTION 2: Read aloud the essay and model annotating.

- OPTION 3: Have students read aloud in pairs or small groups.

- Facilitate a class discussion by asking students the Discussion Questions.

- Tell students the following: “Push factors are circumstances that compel people or groups to leave their current locations, or countries, in order to migrate elsewhere. Pull factors are conditions or opportunities that attract people or groups to a new location or country.”

- Have students complete the concept map on page 1 of the worksheet entitled, “Push and Pull Factors for Bengali Peddlers Arrival in New Orleans.”

- Have students use the lesson essay to list reasons Bengali peddlers came to New Orleans in the boxes. (Have students add more boxes as needed.)

- Have students list the “push factors” in the top row and “pull factors” in the bottom row.

- Ensure students understand the meanings of the following terms and then have them mark each box (with the push and pull factors) with the label that best categorizes the cause:

- E - Economic (related to the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services)

- G - Geographic (related to the physical features of an area)

- P - Political (related to systems of power, government, or public affairs)

- C - Cultural (related to the ideas, customs, and social behavior of a society)

- S - Social (related to society, its organization, and how people interact or relate to each other)

- Divide students into five small groups. Assign each group to conduct further research on one of the categories listed above (i.e., economic, geographic, political, cultural, social). Have each group complete the corresponding row in the chart on page 2 of the worksheet entitled, “Push and Pull Factors for Bengali Peddlers Arrival in New Orleans.”

- Have students list push factors in the middle column.

- Have students list pull factors in the right column.

- Have each group share their findings with the whole class. Have students take notes on their worksheet, adding content shared by their peers.

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Which factor (i.e., economic, geographic, political, cultural, social) was the most compelling push factor for the Bengali Muslim peddlers? Why was this so?

- Which factor (i.e., economic, geographic, political, cultural, social) was the most compelling pull factor for the Bengali Muslim peddlers? Why was this so?

- Show students the video entitled, “Early South Asian Immigration” (stop at 5:35). Have students mark a check next to the boxes on their worksheet that are corroborated by the video. Have students add new boxes with new information from the video. Facilitate a discussion by asking the following questions:

- Why has the peddler network gone under the radar according to Vivek Bald?

- Who was Moksad Ali (1860-1925)?

- Who was Ella Blackman (1871-1927)?

- What does the Ali family’s story tell us about race and the racial hierarchy in the United States?

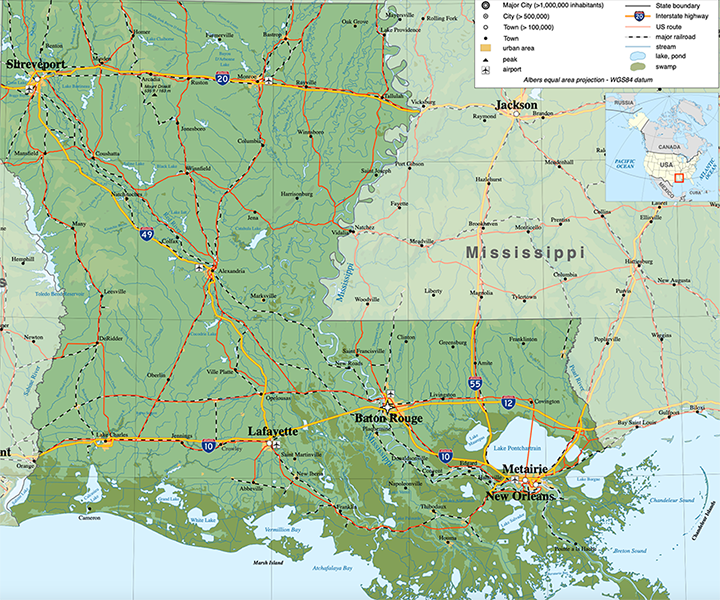

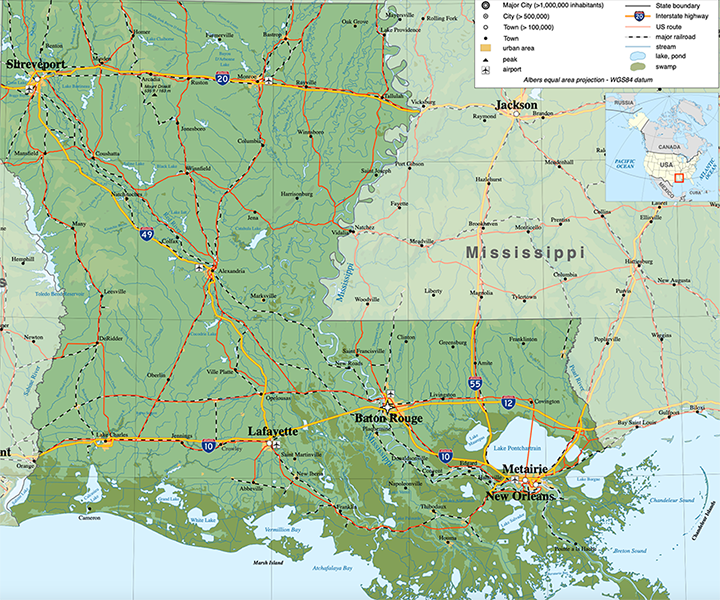

Map of Louisiana.

Activity 3: Examining the Significance of Rivers to New Orleans and Hooghly

- Have students share their prior knowledge and/or prior experiences with New Orleans.

- Ask students: “Why was New Orleans an important hub for Bengali peddlers?”

- Have students look at a map of New Orleans and have them explain how New Orleans’s geographic location made it an important hub. Have students identify some geographical characteristics of New Orleans based on the map. Point out that New Orleans is bordered by the Mississippi River on the south, which leads into the Gulf of Mexico (Gulf of America).

- Tell students the following: “Both Hooghly and New Orleans are cities located on rivers.”

- Have students work in small groups to conduct internet research answering this question: “Why are rivers important for growth and development?” Have students record at least three reasons.

- Have students share their responses and organize their responses into the following categories, recording student responses in this chart which is displayed for all to see:

|

Economic

|

|

|

Geographic

|

|

|

Political

|

|

|

Cultural

|

|

|

Social

|

|

- Facilitate a discussion by asking the following question: “To what extent did the Bengali Muslim peddlers rely on rivers for their trade paths and trade business?”

Many Bengali peddlers settled in Tremé, the oldest Black neighborhood in New Orleans.

Credit: Library of Congress, Photograph by Walker Evans for the United States Farm Security Administration.

Activity 4: Mapping the Routes of Bengali Muslim Peddlers

- Have students highlight all the names of physical locations in the essay. Ask students the following question: “What do you notice about these locations? Why did the Bengali Muslim peddlers choose these locations?”

- Have students create a map of a possible route of a Bengali peddler based on the information in the lesson. Have students select at least 4 significant locations to conduct additional research. Have students write a paragraph for each location explaining the significance of the location for Bengali peddlers.

- Have students add their paragraphs onto the map to create an infographic.

- Have students watch the film entitled, “In Search of Bengali Harlem.” Have students compare and contrast the settlement of Bengali peddlers in New Orleans, Louisiana and the South, with those in Harlem, New York.

- Have students examine how Bengali peddlers navigated the Black-White racial binary (the idea that race in the United States is experienced by two groups, Black people and White people) in the segregated South by reading the article entitled, “The Lost Stories of Bengali Immigrants in the United States.” Have students research the concept of “colorism” and explain how it applies to the experiences of Bengali peddlers in the South. Have students explain how the history of Bengali peddlers in the South challenges and/or complicates the idea of the Black-White racial binary.

- Have students research early peddlers in New Orleans such as Alef Ally, Aynuddin Mondul, Ibrahim Musa, Jainal Abdeen, and Solomon Mondul. Have students write a biography or profile about the selected peddler.

- Have students research the Muslim and Hindu religions and complete a Venn Diagram describing the differences and similarities.

- Tell students that Hooghly is one of the most economically developed districts in West Bengal known for its jute industry. Have students learn more about jute. Have students create crafts made of jute; for example students can weave jute pouches or jute coasters.

- Have students learn more about Tremé and produce a script for a historical tour of the city.

D2.Eco.3.6-8.

Explain the roles of buyers and sellers in product, labor, and financial markets.

D2.Geo.4.6-8.

Explain how cultural patterns and economic decisions influence environments and the daily lives of people in both nearby and distant places.

D2.Geo.6.6-8.

Explain how the physical and human characteristics of places and regions are connected to human identities and cultures.

D2.Geo.11.6-8.

Explain how the relationship between the environmental characteristics of places and production of goods influences the spatial patterns of world trade.

D2.His.14.6-8

Explain multiple causes and effects of events and developments in the past.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.7

Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

8.2

Analyze connections between events and developments in U.S. history within their global context from 1877 to 2008.

8.4

Use geographic representations and historical data to analyze events and developments in U.S. history from 1877 to 2008, including environmental, cultural, economic, and political characteristics and changes.

8.5

Use maps to identify absolute location (latitude, and longitude) and describe geographic characteristics of places in Louisiana, North America, and the world.

8.9.b

Explain the causes and effects of immigration to the United States during the late 1800s and early 1900s, and compare and contrast experiences of immigrants.